I just got back from a Dissertation Writing Retreat, put on by my undergraduate fellowship, Mellon Mays . Twelve of us planned our days, talked goals and schedules, and tried out techniques for staying productive and keeping up our morale. The first two days we were essentially locked in a room for four hours (two sessions of two hours each) and worked on our computers, using social pressure and a shared timer. Then we weaned off to one session and then no sessions, with the expectation that we’d figure out how to use the time schedule ourselves. The end of each day we had check-ins and discussed what worked and what didn’t. So I thought I’d share with you some of the stuff I learned.

#IlookLikeAProfessor #squadgoals (Faculty panel)

First, a few things I already knew:

- Figure out where you can work. When my partner worked from home we turned the guest bedroom into an office for him. I’ve done parks, coffee shops, the office, and our home office and all were much more productive than the kitchen table, where I can see the dishes, the fridge (what’s for dinner tonight?!), the living room…

- Write a task lisk for each day and focus only on those tasks.

- Make sure to “have a life,” which in my case meant starting a baking and math blog.

- Exercise! Figure out some way to move your body.

- Use SMART goals. Specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely. I don’t really know what “attainable” means vs. “realistic” but maybe it balances out people with too low self confidence (at least it can be attainable) vs. people with too high self-confidence (remain realistic!).

N years of grad school and those are the things I knew. I’ve been in a rough space for the past few months, math and life-wise, so this writing retreat was the perfect detox/jump start for me. Here are some things I learned!

- Break up goals into specific, manageable tasks. I used to look at my planner post-it each day and see things like “work on paper X” and “read paper Y.” On our first evening we listed our main goals for the week, and then took the top goal and split it into at least three specific tasks. So my “organize paper” became 1) copy topic sentences (lemma/theorem statements), 2) skim paper and name techniques, 3) figure out which theorems use which techniques, 4) form flowchart, and 5) rearrange paragraphs so flowchart makes sense. Then when I sat down the next morning I didn’t have “organize paper” to look at, but a really easy softball of a task to start my day and feel productive.

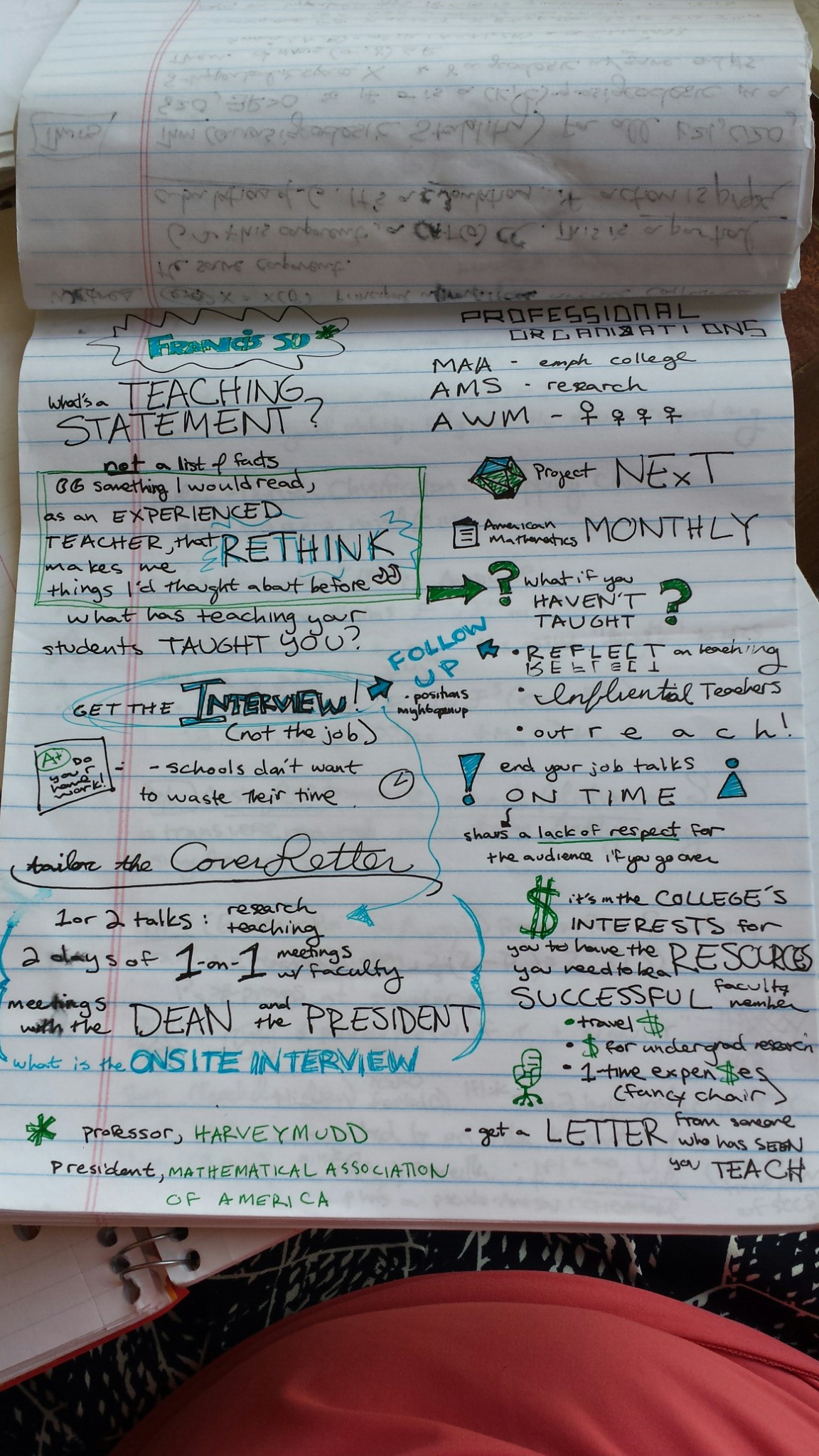

- Set out your tasks and goals the day before. This has helped me SO MUCH. I used to spend half an hour each morning reviewing the previous day and setting up what to do that day. Here’s a picture of the Emergent Task Planner pages we were using.

- Try the POMODORO TECHNIQUE. The idea is that you break up goals into tasks, and then set a timer and FOCUS on each task for 25 minutes (=one pomodoro), then take a five minute break. You fill a little box for each pomodoro (=”pom”) next to your task that you took, and then you cross off the task when it’s done. If your tasks are taking 4 or more poms, you’re not breaking up the tasks enough in step 1. After four poms, you take a longer break (15 minutes). DO NOT SKIP BREAKS. The breaks let you work longer and feel more refreshed and ready- in my experience, if I skipped breaks then I’d do a pom or two less that day. The timer is great! I use a free app on my phone as the timer. I also go one step further and put my computer on airplane mode for the poms when I don’t need the internet. Speaking of which…

- Consider turning off the internet. I was always getting stuck on a thing, and then getting frustrated, and then checking slate or gawker or national review or reason or twitter or facebook and reading an article or five before going back to the task at hand. I’m pretty distraction-prone, so turning my computer to airplane mode and putting my phone away helped a lot during the retreat. In regular life I’ve been setting computer to airplane mode and putting my phone on a shelf after setting the timer (I still need to pick up if daycare or nanny calls).

- Keep a master task list for the project/week/month. We made an “activity inventory” of the larger goals we wanted to accomplish over the week. Then at the end of each day once I had finished my tasks for the day and was looking to the next day, I’d refer to the activity inventory and cross off the major goals and see what was coming up to break into tasks for the next day.

Goals to finish this project, crossed off as I accomplished them. Or, funnily, — if they stopped being necessary.

- Keep track of distractions. The Pomodoro technique recommends putting an apostrophe in your list to show when distractions happen. I did not do that, but I do make liberal use of the “notes” section at the bottom of the ETP sheet above, or a side notebook, just to sketch a few notes about ideas that cropped up. Also, if I got hit by the math muse, I’d run with it and write it down as a new task with little time bubbles (I believe in staying flexible!)

- Various one-time techniques: pre-hindsight: think about a time you didn’t achieve a goal, and try to figure out what would have helped you achieve it. Then try to implement those tools for success in future goals. Put yourself first: spend the best part of the day (the time you’re most awake and aware) on the work that matters to you, and then deal with other peoples’ needs. Take breaks: “You don’t realize you need a break until you’re fatigued, and by the time you’re fatigued it’s too late (to do more good work”-Shanna Benjamin, our amazing facilitator.

Good luck with all your work, blog readers! I think this is also useful for non-solo workers, but it’s harder to keep track of because there will be other people and other schedules involved. I did meet with a fellow grad student and we pom’d together, including a 25 minute conversation we had trying to figure something out. Good luck to all of us!